Relocating South Korea’s Capital: Sejong City and the Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture

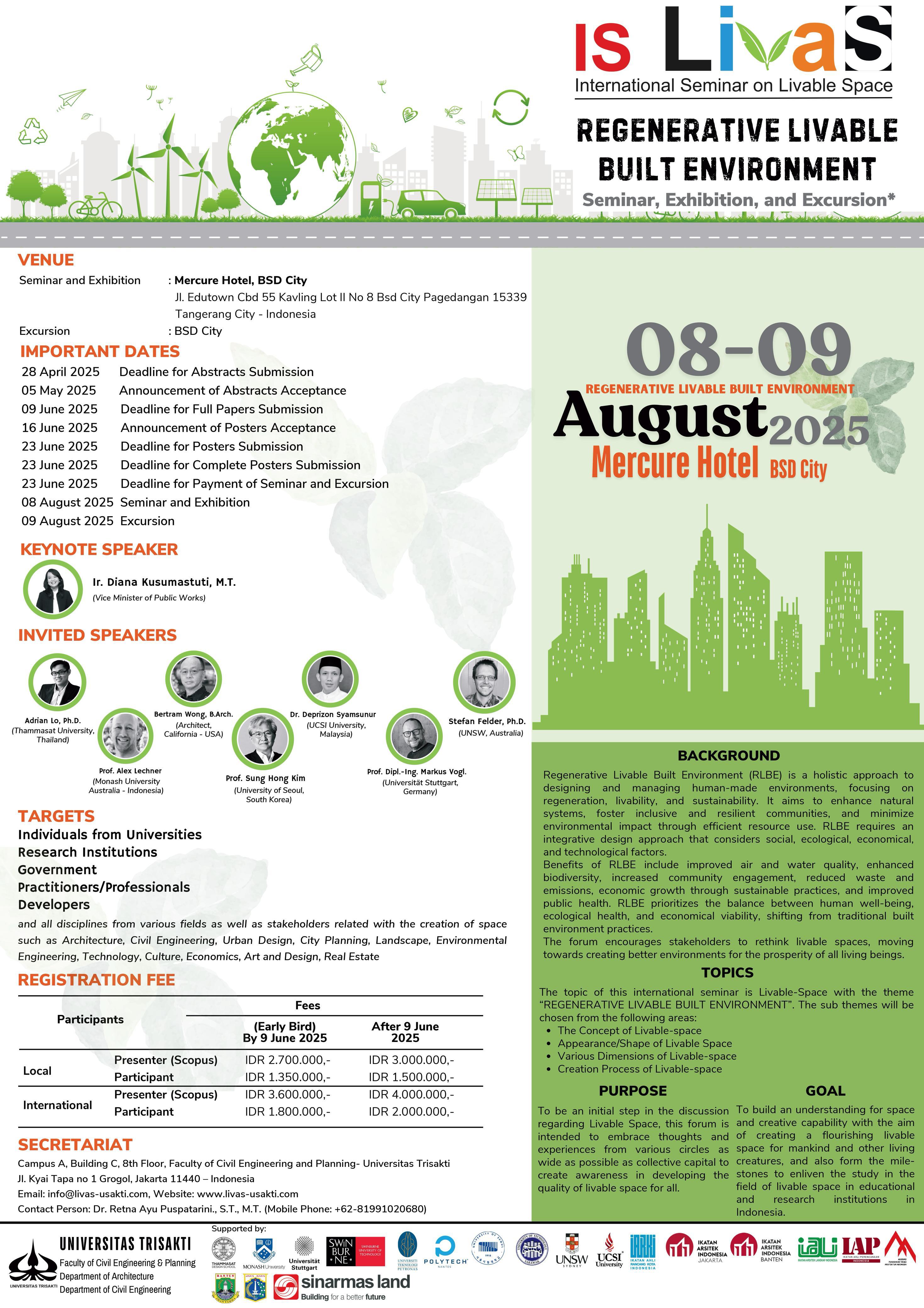

4th International Seminar on Livable Space, BSD City, Indonesia, August 8-9, 2025

Sung Hong Kim, Professor of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Seoul

Abstract

Megacities face challenges in becoming safe, inclusive, and resilient, while new towns struggle to reach the critical mass needed for economic and social viability. As a result, relocating a hyper-concentrated capital to a newly planned town presents a very different planning agenda—and there have been few successful examples of capital relocation in modern and contemporary urban history.

In South Korea, the relocation of the capital has been an ongoing issue since the 1970s, primarily for national security reasons—to move the frontline with North Korea, as well as key communist allies, farther south of Seoul. However, after the 2000s, the focus shifted to redistributing resources concentrated in the Greater Seoul Metropolitan Area (GSMA), where 26 million people—half of South Korea’s total population—live. Seoul is located only 50 kilometers from the DMZ.

Sejong City was initially planned as the new capital in 2003, and it is located in central South Korea, about 120 kilometers south of Seoul. However, following a series of political debates, the Constitutional Court ruled that the capital relocation was unconstitutional. Consequently, the city was downgraded to a Special Administrative City.

The Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture (KMUA) is one of them. An international design competition for KMUA was held in 2020, and was won by AZPML and UKST. The museum was envisioned as a scaffolding-like structure that boldly expresses the constructional and tectonic aspects of architecture. The 22,000-square-meter building includes 6,000 square meters of exhibition galleries, along with educational, multimedia, workshop, and archival facilities. The archive, to be shared by five museums, is connected to the underground floor of the KMUA.

The KMUA project is being carried out within a complex governmental structure. The Sejong City Construction Agency oversees the design and construction, while the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MLIT) manages the collection and exhibition. Within the MLIT, a small ad hoc team has been formed, supported by the Architecture & Urban Research Institute.

In 2021, the MLIT appointed a director for the inaugural exhibition. The director oversees the project, working with curators, researchers, and the agencies responsible for fabricating and installing the exhibits. More specifically, the director's role includes coordinating with architects and contractors, researching the history of Korean urban architecture, curating the opening exhibition, helping with the collection and archiving of significant artifacts, and supporting the ad hoc team’s transition into an independent organization.

From a curatorial perspective, the fundamental problem of an architecture museum lies in the impossibility of bringing actual buildings into a museum space. Visitors are typically presented with scaled-down models or reproductions, resulting in displays that often feel explanatory or didactic. The challenge lies in bringing the aura of excitement that an original ‘artwork’ in an art museum typically evokes.

The curatorial strategy was built on five key approaches: 1) balancing an interactive approach for laypeople and in-depth critical analysis for academics and experts; 2) blending diachronic and synchronic presentations; 3) exploiting the naturally lit high ceilings to display full-scale building elements; 4) anatomizing and revealing visible and invisible elements of buildings and cities; 5) creating the experience of abrupt shifts in the scale of buildings and cities.

The title of the inaugural exhibition is "Korean Urban Architecture, 1950–2010: Building Life After the Korean War." After 2025, the temporal scope will be expanded to include the colonial (1910-1945) and pre-colonial periods, and the geographical boundary will be extended from South Korea to the Korean peninsula and East Asia.

The curatorial team defines urban architecture as an inseparable physical entity encompassing urban form and architecture, which can be manifested at a visible and tangible scale, and views urban architecture as a product of political, social, and cultural forces shaped within economic, legal, and technical constraints. The team aims to engage the general public with a story of perseverance and growth through the display of cultural heritage artifacts and experiential installations. It also raises awareness of current global urban architectural issues and seeks creative, innovative solutions.

The exhibition focuses on the interaction among three key players: 1) the government, which plans and executes projects and supports industries under a national agenda; 2) the professionals (planners, architects, and engineers) who perform activities based on their knowledge, skills, principles, and creative will; and 3) the citizens who seek a better life in the built environment of the city.

The 10 sub-theme exhibitions follow a common narrative structure: 1) What were the political, ideological, social, and cultural forces behind urban architectural development? 2) Who, when, and how were the spaces and forms made? 3) How were the lives of citizens affected by urban architectural development? 4) Are there universal values beyond regional, national, and geographical boundaries?

As of 2025, four different projects are underway simultaneously: construction, collection, exhibition, and establishing an independent organization. Between 2022 and 2026, a total budget of 69 million USD is allocated for building construction, 16 million USD for collection, and another 21 million USD for exhibition.

The fundamental question, “What is an architecture museum?” is inherently interconnected with cities, places, and buildings. While images, drawings, and information on architecture can also be transmitted through books, magazines, and social media platforms, the end product of architectural design is the building, which is specific to its site. It is anchored to the land. Architectural knowledge is mobile, but architecture itself is immobile. The role of an architecture museum involves the two facets of architecture: mobility and immobility.

Due to this immobility, the architecture museum must address both synchronic and diachronic approaches in a twofold manner. First, the museum represents the ‘here and now’ of the city and place. Second, it embodies the collective memory of the city and place.

In Asia, the reinterpretation of history is inevitably related to 'Modernism.' The language of modern architecture became firmly established as a new classicism in Western Europe and was disseminated to non-European countries as dominant forms and styles until the 1950s. Architects in Asia have been under constant pressure to search for and find their cultural DNA from the past, and at the same time, have tried to translate and transform the architectural language of modernism into the context of the ‘here and now.’

In this context, the museum can become a platform for the critical interpretation of history and discourse by opening a dialogue in Asia—a dialogue about ideologically, politically, and socially sensitive issues such as imperialism, colonialism, colonization, communism, the Cold War, and dictatorship.

The KMUA, scheduled to open in spring 2027, will be the first national institution dedicated to collecting, managing, preserving, and researching urban and architectural heritage and materials, as well as educating and engaging the general public through exhibitions.

For the residents of Sejong City, it will be a hub for cultural activities that overcome locational disadvantages. Depending on its outcome, it could serve as a valuable reference for new capital planning, including Nusantara in Indonesia.